A legal design case study: Privacy policy

A legal design case study: Privacy policy Read More »

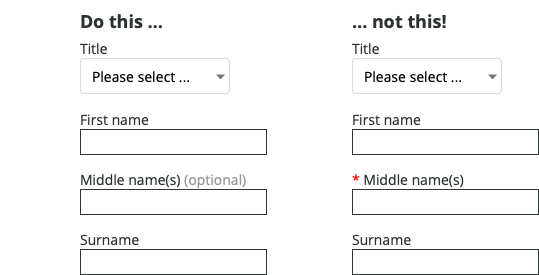

We’re currently working with a client on a design system to normalise their user interface design. As their software makes extensive use of forms, these have been the subject of considerable discussion, and NNG’s video on marking mandatory fields was shared as part of this.

It’s not often we take issue with NNG, but this is one area where their recommendation to mark mandatory fields with an asterisk is based on poor reasoning. They start out by saying that users don’t read instructions at the top of the page in forms. Absolutely correct! Messages at the start of the form will generally be ignored, so to say ‘Mandatory fields are marked’ or ‘Optional fields are marked’ is a waste of time.

They then say that users will scan the entire form to check for which fields are optional. Wrong! Their initial statement that user just jump in to completing a form is correct. And while users won’t usually read instructions at the top of the page, they will read form labels just before completing the form element – otherwise how else do they know what information they need to provide?

There are 2 things to consider here. The first is how forms are typically designed. Most form elements are mandatory: both form designers and users stay focussed on the task at hand rather than adding information that isn’t of direct value. The second is tone of voice, which we believe is vital. Marking mandatory fields, sometimes in red, affects the tone of voice of the form, and hence the relationship with the user. Imagine the organisation as a person, talking the user through the form. Each asterisk is like the person stabbing a finger at the field and demanding that the user complete it. As the user comes to the form with the expectation that most, if not all fields, are mandatory, then demanding the user do something they expected to do anyway will reduce any positive impression given by using tone of voice well elsewhere! Contrast this with marking optional fields: this is more like having a smart friend helping the user complete the task because they understand how the user is working, and wants to help them get the job done.

In this example, marking ‘Middle name(s)’ as optional lets the user read the label first, then decide if they want to provide the information. The different styling for ‘(optional)’ provides an additional visual cue that the field is optional which the user can quickly learn to recognise.

Marking optional fields Read More »

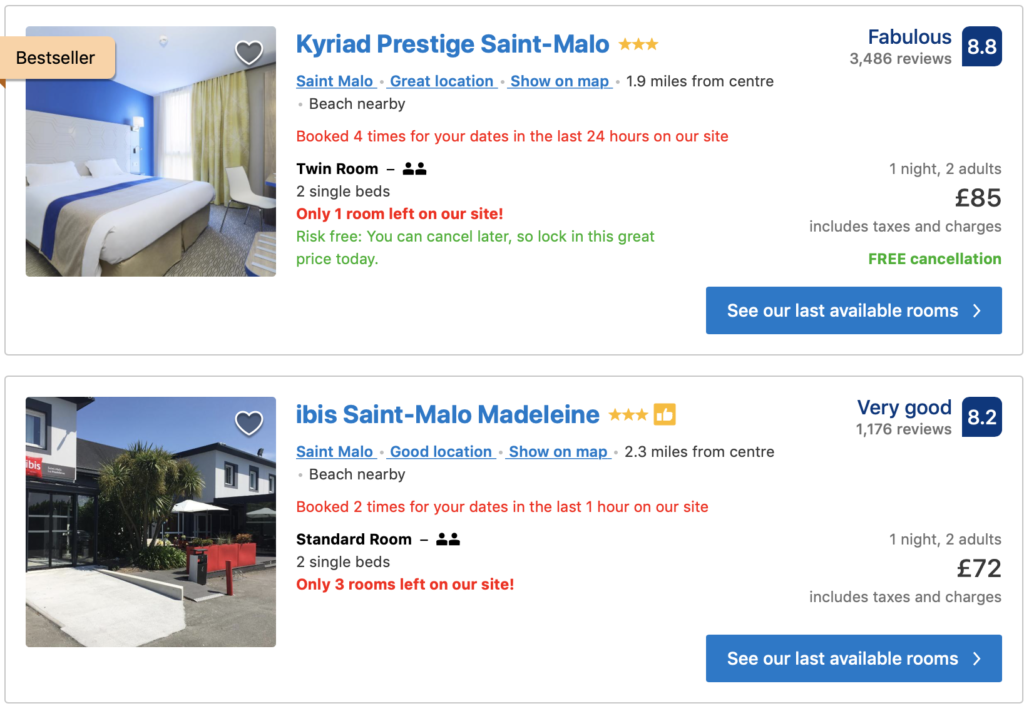

Behavioural tools are incredibly useful in designing experiences, and one of these is scarcity. From behavouraleconomics.com:

When an object or resource is less readily available (e.g, due to limited quantity or time), we tend to perceive it as more valuable (Cialdini, 2008). Scarcity appeals are often used in marketing to induce purchases. Marketing messages with limited quantity appeals are thought to be more effective than limited time appeals, because they create a sense of competition among consumers (Aggarwal et al., 2011). An experiment (Lee & Seidle, 2012) that used wristwatch advertisements as stimuli exposed participants to one of two different product descriptions “Exclusive limited edition. Hurry, limited stocks” or “New edition. Many items in stock”. They then had to indicate how much they would be willing to pay for the product. The average consumer was willing to pay an additional 50% if the watch was advertised as scarce.

As with any tool, this can be misused. Booking.com has been accused of misleading customers by giving false accounts of the popularity of rooms, in an investigation by Which?. The approach booking.com was using was to say there was only “1 room left” for a given type of room, when in fact there were multiple rooms available.

The impact of this is to pressure the user into making a purchase.

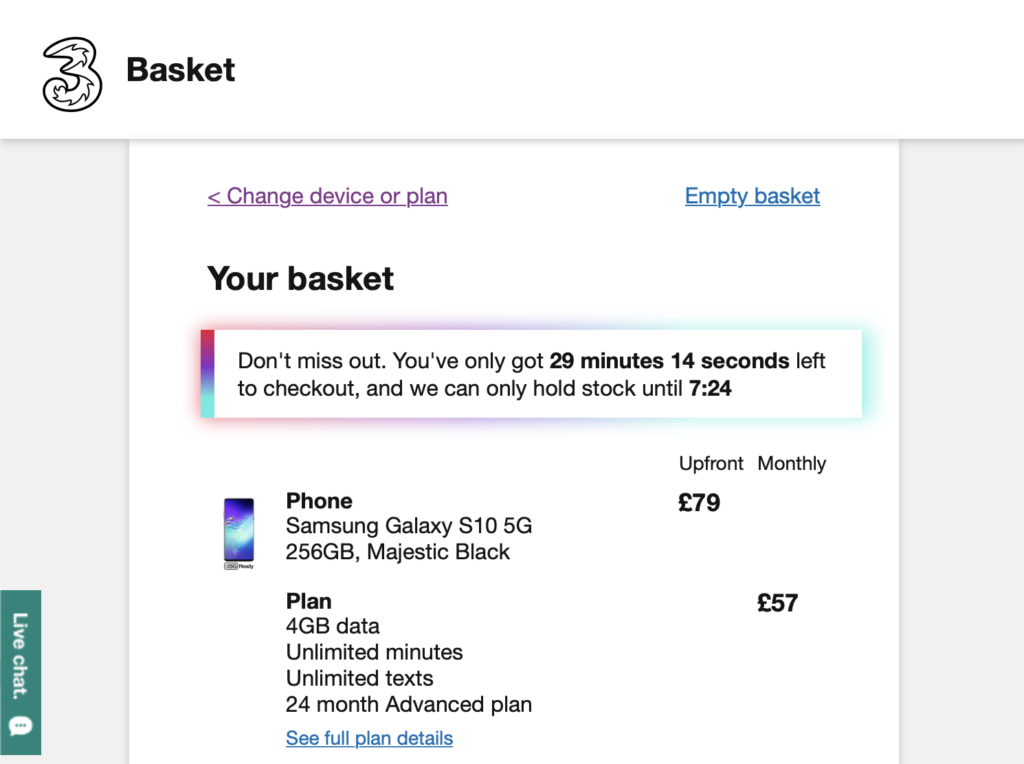

booking.com is not alone in using this type of behavioural approach – Three uses a countdown timer to encourage the user to make a decision:

There is nothing inherently wrong with using behavioural approaches in UX design. In some circumstances it has been found to work extremely well. For instance, in organ donation, where countries automatically opt people in, roughly 80% of people donate. Where countries automatically opt people out, roughly 80% opt out. As organ donation is a positive social good, automatically opting people in would seem to be a positive step.

The question for UX designers is when encouragement passes over into pressure – what could the negative impact be on the person? While I wouldn’t necessarily go so far as to suggest designers need their version of the Hippocratic oath, open discussion about what designers responsibilities are can only encourage more responsible decision making.

Behavioural tools in design Read More »